I can’t remember when I first heard about, met or read Weng Pixin’s comics, but I suspect it got to do with Andrew Tan/drewscape. He drew this comic about us visiting Pixin at her Bali Lane shop.

That's a long time ago and I think drew had a crush on Pixin, but what do I know?

In any case, I bought many of her early mini comics, read them and this was my assessment of her works back in 2012:

Weng Pixin is a 28-year old artist who graduated from the Lasalle College of the Arts in Singapore in 2004. She sells her own handmade toys from recycled materials in a shop she opened in 2008. Currently she also teaches part time at Lasalle on how to draw comics.

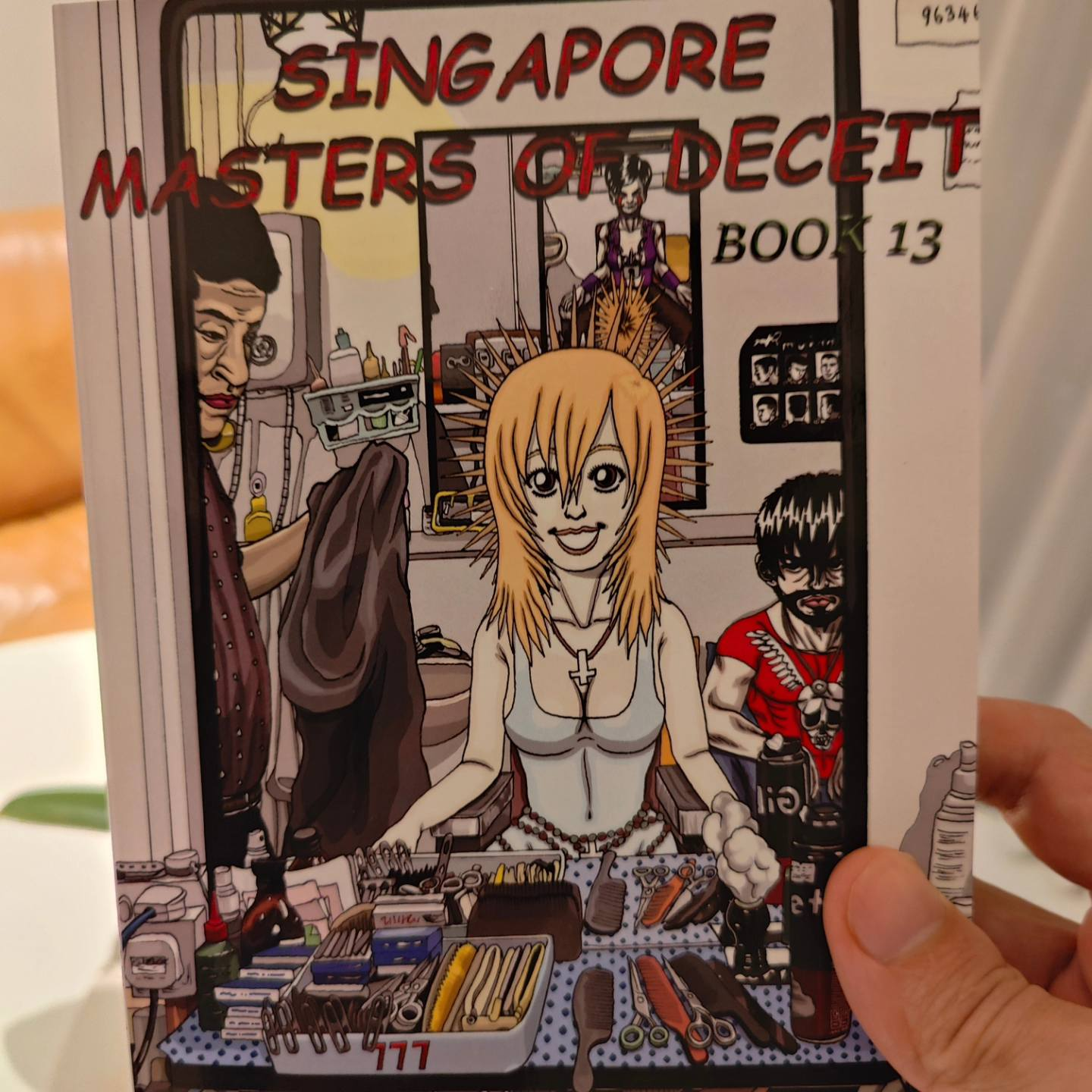

Pixin, as she is known, is not a professional comic artist. But she has created a few mini comics over the last few years, which she sells at her shop and book shops like Books Actually. At last count, she has made 8 mini comics and 3 poster comics.

Pixin did not want to be interviewed for this paper so I do not know her print run, sales or target audience. But according to Books Actually, there is no fixed demographic for those who bought Pixin’s comics. About 20 to 30 copies were sold over a one-year period, which was decent for a zine or mini comic in Singapore. But there is no way Pixin is depending on her comics to make a living even though they are priced at SGD$10 and above, double the price of most other mini comics in Singapore.

Pixin’s influence are Harvey Pekar and Jeffrey Brown. She seeks to emulate the emotional and intellectual intensity of the former but is closer to the latter’s lovelorn remembrances.

Pixin does some fictional works, but her major comics so far are the 2-parter, Please To Meet You and I’ve Lost An Ocean, which detailed the fallout of her breakup with her boyfriend in 2006.

Pixin described these 2 works as diary-entries, and doing these comics is meant to be therapeutic for her. In the afterword, she said she was advised by family and friends to not be overly edited. Thus, Pixin’s comics falls within the category of what Hillary Chute described as reimagining trauma, whereby artists return literally to events to re-view them.

In that sense, Pixin is in good company. Some of the best comics by female artists are autobiographical ones about relationships. More specifically, father-daughter relationships: Fun Home (2006) by Alison Bechdel and You Will Never Know (2009) by Carol Tyler.

Pixin does not have issues with her father. (the father made a rare appearance in I’ve Lost An Ocean to ask how she is) But she is left wondering why her boyfriend broke up with her. At the end of the 2 books, she and us are still in the dark about that. No real reasons were given. We catch a few glimpses of the boyfriend in the comics, but he remained a mystery man.

The first book, Please To Meet You is a blow by blow account of the fallout. But obviously one book is not enough. The catharsis is incomplete. The second book, I’ve Lost An Ocean is more reflective. It takes place immediately after the events of Please To Meet You – it shows how Pixin picked herself up, recovered from the experience and reconciled with the breakup. She still described her boyfriend as kind and gentle even though she was dumped for no good reason. And truthfully, she presented us with no reasons. There are no answers, just ellipsis.

---

While I presented the above (very raw) analysis at a comics conference in Hanoi, they were never published. Reading them now, I think ellipsis, whether intentional or not, has become a narrative trope of Pixin’s. You don’t have to explain everything. Some things happened for no reason. You just got to let go and accept.

Since 2012, I continue to follow Pixin’s works, buying them when I can find them. I finally got a chance to interview her in 2016.

http://singaporecomix.blogspot.com/2016/11/illustration-arts-fest-singapore.html

(mm…I have reused what I wrote above in the interview)

I moderated Pixin in comics panels at the Singapore Writers Festival in 2019 and 2020. The latter was about her book, Sweet Time, which I reviewed for my friend’s Paul Gravett’s website. Here’s the review:

Wendy Pixin is the first Singapore comic artist to be published by Drawn & Quarterly, so that is a big deal. Pixin has been making her heartbreak comics for more than a decade and she has grown over the years. She still pours her heart out, but it is more controlled with a stronger sense of narrative and the use of colours to widen the palette of emotions of this cruel thing called love (before her zines were in black-and-white). The stories in Sweet Time can also be classified under travelogues, as they are vignettes of leaving things behind and sorting out your emotions in a foreign land. I asked Pixin if travelling is a way of leaving your problems behind. She replied, you can’t, you carry them with you wherever you go.

http://paulgravett.com/articles/article/best_comics_of_2020_an_international_perspective_part_1

That’s pretty much brings us up to date to 2021 with the publication of Pixin’s second book with Drawn & Quarterly, Let’s Not Talk Anymore, which is about her matrilineal line - her mother, grandmother, great grandmother and her yet to be born daughter.

While Sweet Time is a collection of Pixin’ stories she created when she was 25 to her early 30s, Let’s Not Talk Anymore is an ambitious long form narrative that cris-cross time, space and emotions. Nothing quite like anything we have seen in Singapore comics. So I wanted to interview her again.

---

Q: I first heard about this project at our panel at the Singapore Writers Fest in 2019. How did this book come about and what made you want to do such a book?

I wanted to think about the figures along my matrilineal line because I knew very little about my mother’s side of the family. It became quite clear that they - the women along my matrilineal line- came from a time, culture and environment that discouraged them from developing the ability to communicate and express their internal world. I see the negative consequences of that manifest in their discomforts in communicating their needs and desires in the present times. This has also led little to no meaningful stories being passed down from one generation to the next. So art came in to help me acknowledge and address this gap.

The matrimonial line:

Kuan (great-grandmother) - who left China for Singapore in 1908 at age 15

Mei (grandmother) - abandoned by Kuan and adopted by a seamstress in 1947

Bing (mother) - a student in 1972 who has to take care of her two younger brothers. Her mother, Mei is a bitter woman.

Bi (aka Pixin) - a moody student in 1998. She doesn’t get along with her mom, Bing.

Rita (imaginary daughter) - Bi’s daughter in 2032 who hangs out with her cousin, Solar. Rita also visits her aunty (Solar’s mom).

Q: In 2032, Rita recalls coming across a big leaf with her mom (that's you, Pixin). And that leads to a discussion on water, blood and family ties. "Everything must start somewhere." I am curious. Why is it important (for you) to know who was at the start and to start somewhere…?

I am generally curious about a person’s story - how they have come to be in different stages and in different moments of their life, in the choices they make…in the choices they don’t make. In particular to “Let’s Not Talk Anymore”, in the choices they cannot make. I like to think about the layers of reasons behind that, and wanted to find a visual metaphor to represent those cycles or paths, in reference to Rita’s big leaf moment.

There’s almost no negative outcome I can think of, in the pursuit to understand one’s past. Even if something felt to be unpleasant or soul-crushing be discovered, I reckon it can only serve as lessons to be made sense of, and to give us opportunities to learn something in order for us to be better people to ourselves and to others in the present moment. In the comic, Rita was created to express these sentiments.

Q: In 2032, Rita wanted to draw from memory. Pixin, did you draw from memory and did you draw from memory?

Rita’s interest to “draw from memory” was perhaps my way of saying: our memory shifts, our memories are not an exact replica or copy of what had happened a second ago…or a generation ago. Every time we recall a memory, we have reshaped our narratives with time, with bias and with our internal emotional landscapes. Rita and Solar’s conversation on memory earlier on in the book was also a way (for me) to say: This is not an autobiographical story, but rather an imagination and glimpse into these characters’ lives at the typically tumultuous age of 15.

Q: On this topic of drawing, in 1972, when Bing first appeared with her younger brothers and walking with them to school, she is drawn way much bigger than them. Almost like a giant. I take it that this perspective is intentional?

Why the flatness as an artistic style / choice? I kept looking at the image of Bi drawing at the table in 1998. (when she spilled her water and her mom was kind to her) The squares on the floor just accentuate the flatness of the drawing.

I’ve always been drawn to art that are composed of flat shapes and colours (such as the motifs found in ancient Peruvian textiles), or art that leans towards unrealistic perspectives or are visually ‘off’ in certain ways. As an art student, I loved art made by outsider artists (and I still do!). I remembered subscribing to RAW magazine, a magazine that provided tons of information on outsider art. I was always immensely happy when a new copy has arrived in the mail. I found myself drawn to Henry Darger’s works, where his drawings are composed of a mix of tracings that he had made from found printed materials, alongside drawings of his own. Darger would arrange them one over the other or side-by-side, creating a world that was chaotic, incredibly beautiful and intricate.

I imagine working with children as an art teacher has also influenced me to find inspiration in carefree approaches towards picture-making. I’m always in awe of how children’s style of mark-making and line-drawings take on very unexpected routes. It is impossible to copy children’s drawings! It is quite similar to the drawings made by adults who have very little art experience. I usually find those drawings kinda special to look at, as they have been made using a different set of decision-making sequences.

A funny story to this, is how I once took a picture of a drawing that my colleague had made while she was on the phone. My colleague did not come from an arts-based background. So she drew this smiley face while concentrating on her phone call. I took a photo because there was just something about the way she had drawn that smiley face…that looked and felt extra right and extra goofy. She wasn’t convinced when I told her I really liked her drawing, as she knew of my art and the work I do. I replicated her drawing in front of her, and tried to tell her why my replica did not capture the goofy essence that I see in hers. She was still not convinced (haha) but was definitely flattered that her smiley face won a fan.

Q: As much as the book is about mothers, it is also about absent fathers. In 2032, Rita recalls her grandfather, who is Pixin's father. But he is no longer around by then. In 1972, Bing misses her father. Her mom said to her, "People come and go. That's life. No point crying." You thanked your own dad at the back of the book for instilling in you a sense of curiosity in your storytelling. Why the focus on mothers in this book? Or will there be a book about fathers in the future?

The inspiration at the root of “Let’s Not Talk Anymore” is my frustration with the lack of stories through the generations along my matrilineal line. I’ve always been drawn to depicting the dysfunctions in life and in particular - relationships between people who are complex and contradictory. While my father’s chirpy and curious personality has always been a source of comfort and support for me, it hasn’t quite resonated into an inspiration for a story yet.

Q: 1998 - growing up is hard. Being a teenager is tough. The adults don't understand you. You just listen to Smashing Pumpkins all the time. You don't even understand yourself, like why you are crying. How long did it take you to grow out of melancholia? Or not.

One of the things I was interested to explore in “Let’s Not Talk Anymore” is a person’s capacity to attend to others’ emotional needs. This can be learnt from how our own emotional needs or feelings had been attended to during our developing years. Referring to this particular segment you’ve picked up on, my character Bi is frustrated with her mother Bing’s conflicting behaviour: Bing has been shown to be rather cold, and generally unable to attune to Bi’s needs, yet demands Bi to speak up. In Bing’s own story, we noticed that her mother Mei, is dismissive of her troubles and hurt. Same goes for some clues left in Mei’s story, I wanted to capture a pattern of emotional unavailability that’s been passed down from mother to child. I chose mothers rather than fathers because of my personal experiences and observations of my mother, because of my interest in women’s lives of that particular period (1890s - 1970s) and because in that particular time frame, primary caregivers within a household tended to be mothers or female caregivers.

Q: In 2032, Rita and Solar were chatting. Solar talked about how her mom felt stifled while growing up. Is it bad to pretend we are fine when we are not?

I generally avoid thinking whether something is good or bad, where it is much more helpful to tease those out a little. I think it can be a survival and coping mechanism to “pretend we are fine”. In certain situations, it can be vital. For example, if you are in a life-threatening situation such as an abusive relationship, it may be necessary to “pretend we are fine”, just so you can be intact in order to strategise an exit. In a less intense example, it might be helpful to“pretend we are fine” after a disagreement with a friend. This can be a necessary momentary pause from the tension.

In reference to Solar’s statement about her mother feeling stifled and “pretended everything’s fine”… there is little to no good that comes from prolonged periods of being discouraged to communicate, especially when you’re being censored by the very person whom you’re suppose to trust. In this scenario, pretending does more harm than good, because in pretending- you learn to believe your words and your life don’t matter enough, and that ultimately the love you receive is conditional.

Pretending one is fine is a very complicated thing and in certain ways, exploring that complexity is part of the reason I worked on “Let’s Not Talk Anymore”. Whatever form of “pretending we are fine” takes, it is always due to a lack of communication.

Q: In 2032, Rita and Solar talked about what life would be like to live in a world where you have no control over your life. But is it possible at all to have control over one's life? Or is it an illusion?

For “Let’s Not Talk Anymore", I wanted to talk about a certain kind of lack-of-control, one that emerges in the lives of women who felt small, hidden and forgettable.

This was said in reference to Rita and Solar talking about female figures along their matrilineal line living in the times of 1800s - 1970s, women who had very little opportunities to live a life where they can thrive as individuals due to many reasons such as poverty, gender and cultural beliefs, to name a few examples. This is still a very grave problem in some countries around the world in the present moment. A woman facing these particular set of circumstances will have no control over her own life. This one life she has would be defined, affected and dictated by a person of power, of resources and whose voice maintains the status quo.

Q: I read through the whole book and realized that Bi is missing in 2032. She is referred to and appeared in a flashback when Rita was younger (finding the big leaf). Why are you missing in 2032? (just like Solar's observation that Kuan's life is missing in the family photo album)

"All we're left with are the missing pieces and stories."

I wanted a world where not everything’s wrapped up or have a definite conclusion. So I made the decision to leave some characters absent in some segments. I liked the ambiguity and the guesses one makes when encountering the missing pieces, as I myself wondered along those similar paths when working on “Let’s Not Talk Anymore”.

Speaking of missing pieces, one lingering thought that came up when I was working on the book was: If my great-grandmother had come from an affluent background, then she might have stood a better chance of having had a photograph taken of herself and her family. And us living in the future would have a physical object or memento of hers to hold onto and cherish. Without her stories or clues, I was left to do my own style of research.

The research process for Kuan and Mei’s stories were actually fun. One of the processes involved googling for images into an olden time period and location. For Kuan, it was farming in China in the 1890s, and for Mei, it was Singapore in the 1950s.

Curious about what farming life might have been like in China in the 1890s, I remembered searching “do farmers have hobbies or pets?”, and came across an article that talked about how children of farmers in the 1800s might keep crickets or grasshoppers (or some other legged insect found in the fields) as pets by tying a string around the insect’s legs. Although I wonder how an insect (or insect’s leg) would survive a string tied to it, I found the detail fascinating and so included that in Kuan’s story: of her having a bug companion to help lighten everything else in her story.

---

Pixin did not answer all my questions. But these are some of my concluding thoughts about Let's Not Talk Anymore.

In 1972, Bing was ill and her dad paid attention to her. Her parents quarreled. Her mom said, "It's like, I think I am looking at what's in front of me, but then it changes the second I look away from it" Then Bing was jotted back to the 'present' in her art class. Her classmate said to her, "Maybe I wasn't looking at it closely enough in the beginning."

To me, that's a function of art - to capture the subtle changes when one is looking away. The artist tries to capture a glimpse of the real. But it is just a glimpse as none of us can see the whole elephant, just like the children feeling the different parts of the elephant. Some are even blindfolded!

In Let's Not Talk Anymore, Pixin plays with time and our sense and perception of time and narrative.

---

The ties that bind and the threads of time - almost all the characters in the book at one point or another were weaving, sewing, drawing. It ties the whole book together, this image of creativity, domesticity and femininity. Community is obviously important to Pixin. And she has said she finally found her tribe with Chicks on Comics, an international feminist group currently composed of five cartoonists from Argentina, Portugal and Singapore.

As Rita says goodbye to her aunt, she said, "It was lovely making the space to wonder about the women who made us."

Thanks, Pixin, for the interview.